The 500 km/h train racing through Japan's Southern Alps

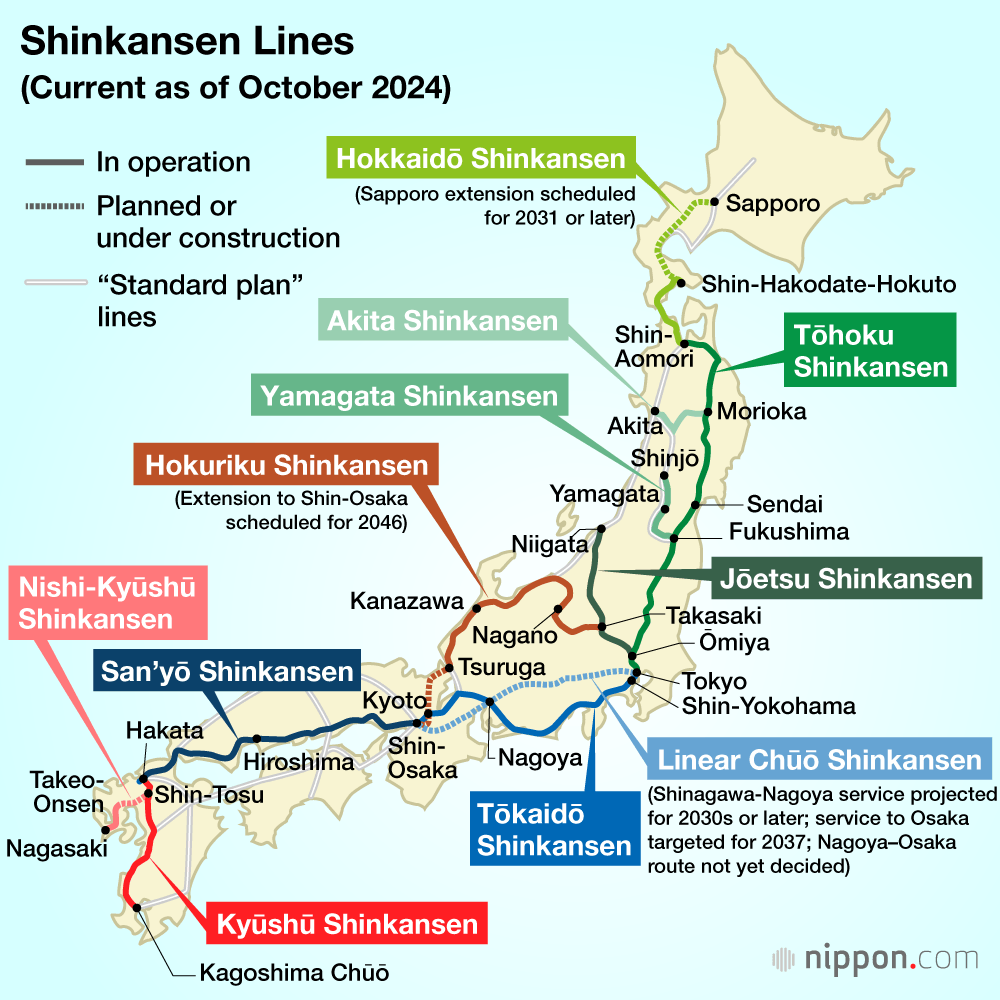

Japan's Chūō Shinkansen maglev promises to slash journey times between Tokyo and Nagoya to just 40 minutes.

Welcome to another issue of The Off Site!

Beneath the mountains of central Japan, engineers are tackling something extraordinary: the Chūō Shinkansen maglev.

It’s part of Japan’s network of superfast shinkansen (bullet trains), and promises to slash journey times between Tokyo and Nagoya to just 40 minutes.

With 86% of its 286km route running underground — including a 25km stretch beneath Japan’s Southern Alps – this project combines massive tunnelling challenges with cutting-edge magnetic levitation technology.

But the ¥9 trillion ($60 billion) megaproject also faces serious obstacles that have pushed its completion from 2027 to at least 2034.

Let’s break it down.

A 603 km/h train

The Chūō Shinkansen uses Superconducting Magnetic Levitation (SCMAGLEV) technology, allowing the shinkansen trains to float 10cm above the guideway. During testing in 2015, a prototype reached an astonishing 603km/h.

This means developing a totally different infrastructure from conventional rail — precision-engineered guideways, superconducting magnets, and specialized power systems.

Putting all this inside deep tunnels – while maintaining safety systems, proper ventilation, and emergency evacuation routes – adds another layer of complexity to an already challenging project.

Stations below stations

The most striking aspect of the Chūō Shinkansen is the sheer scale of its underground construction. According to Japan Railpass, “Almost 90% of the 286-kilometer line to Nagoya will be built through tunnels or underground.”

The current Tokaido Shinkansen runs mostly above ground, but geological challenges and urban density have pushed the new line deep below the surface.

That means that a key challenge is building this faster, underground line without disrupting the existing network. At Shinagawa and Nagoya, new shinkansen stations will be built directly beneath active rail lines and stations.

Tunnelling through fault lines

The entire route crosses some of Japan's most complex geology, including major fault lines – the Central Structural Line and the Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic Line. These create zones of fractured, unstable rock that make tunnelling much harder.

Different sections present unique challenges. Near the Fujino-Aikawa Structural Line, the rock is extensively fractured. On the other hand, the Southern Alps section has high-quality sedimentary rocks alongside sections with serpentinite – a material that expands and puts serious pressure on tunnel structures.

The tunnel will reach depths of approximately 1,400 metres below the surface, requiring specialised excavation techniques and equipment. That also means a lot of testing. JR Central (Japan’s main high-speed-rail operator for the central region) has already drilled pilot tunnels ahead of and parallel to the main tunnel to check geological conditions before the main excavation.

High-pressure groundwater is another big hurdle. Engineers expect "rock deterioration due to pressure and large volumes of water seepage" in several sections, requiring specialised reinforcement techniques.

Excavation at scale

The sheer quantity of excavated material presents some pretty unique logistical challenges. The Tokyo-Nagoya section alone will generate enough excavated material to fill the Tokyo Dome stadium 45 times. Environmental advocates have drawn attention to the fact that JR Central hasn’t yet decided where all this excavated rock will be permanently placed.

Major construction companies including Kajima Corporation (leading tunnelling and depot construction), JR Tokai Construction/Tobishima Corporation (joint ventures for stations and depots), and Shimizu/Obayashi Corporations (key partners in urban tunnelling) are developing specialized techniques to address these unique challenges.

Importantly, these concerns aren't merely technical — they've become politically contentious. In Shizuoka Prefecture, former Governor Heita Kawakatsu blocked construction permits for over a decade, citing risks to the Oi River's water supply. The Oi is critical for local agriculture, particularly for the tea industry that represents 36% of Japan's total production.

Timeline and current status

The Japanese government approved the project in 2011, and construction began in 2014. As of early 2025, it's only about 15% complete overall, with some sections racing ahead and others at a total standstill.

The 42.8km test track in Yamanashi Prefecture is fully operational, and the Yamanashi section of the Southern Alps tunnel is about 70% complete. But the critical Shizuoka section remains completely stalled due to environmental disputes, and hasn’t progressed since 2016.

These delays have pushed the Tokyo-Nagoya opening date from the original target of 2027 to at least 2034. According to some estimates, 2037 is more likely.

On the other hand, the project’s second phase — extending the line to Osaka — has seen its timeline accelerated. From initial estimates of a 2045 opening, Japan Railpass reports that “the government has pledged to speed up progress on the line and secured extra funding to expedite the process. The Osaka extension is now scheduled to open in 2037."

Escalating costs

Unsurprisingly, costs just keep going up. In 2021, JR Central confirmed an increase in construction costs of ¥1.5 trillion ($13.7 billion), taking the total cost of the Tokyo-Nagoya section to ¥7.04 trillion ($48.1 billion).

JR Central has said this was mostly due to the challenging construction work at terminal stations (¥500 billion of the increase) and the host of geological uncertainties they covered.

The rail company has said it will fund these increases "primarily through operating cash flow and the remaining through loans.” Notably, there’s a caveat: “If the company anticipates that it can no longer ensure sound management and stable dividends, it will aim to complete the construction by adjusting the pace of construction.”

So, even 2037 might be optimistic.

On the pod

This week, Jason and Carlos offer their takes on three critical construction and tech topics.

A look at New York's $5 billion offshore wind farm recently halted by a federal stop work order, and what project suspensions mean for construction teams.

Who's responsible when AI tools provide inaccurate information? The hosts examine the complex relationship between users, technology providers, and legal frameworks.

Should construction tech companies focus on the ENR 400 or the thousands of smaller firms?