Inside Europe's most ambitious rail project

Milan to Paris in four hours — via the world's longest railway tunnel.

Welcome to another issue of The Off Site!

This week, we're diving deep into one of Europe's most ambitious infrastructure projects: the Lyon-Turin high-speed railway.

The project includes the world's longest railway tunnel, cutting through the Alps to connect two major European economies.

It's a project decades in the making, beset by political wrangling, technical challenges, and passionate opposition — yet it continues to advance toward completion.

Let's explore the twists, turns and breakthroughs of this monumental undertaking.

Milan to Paris in four hours

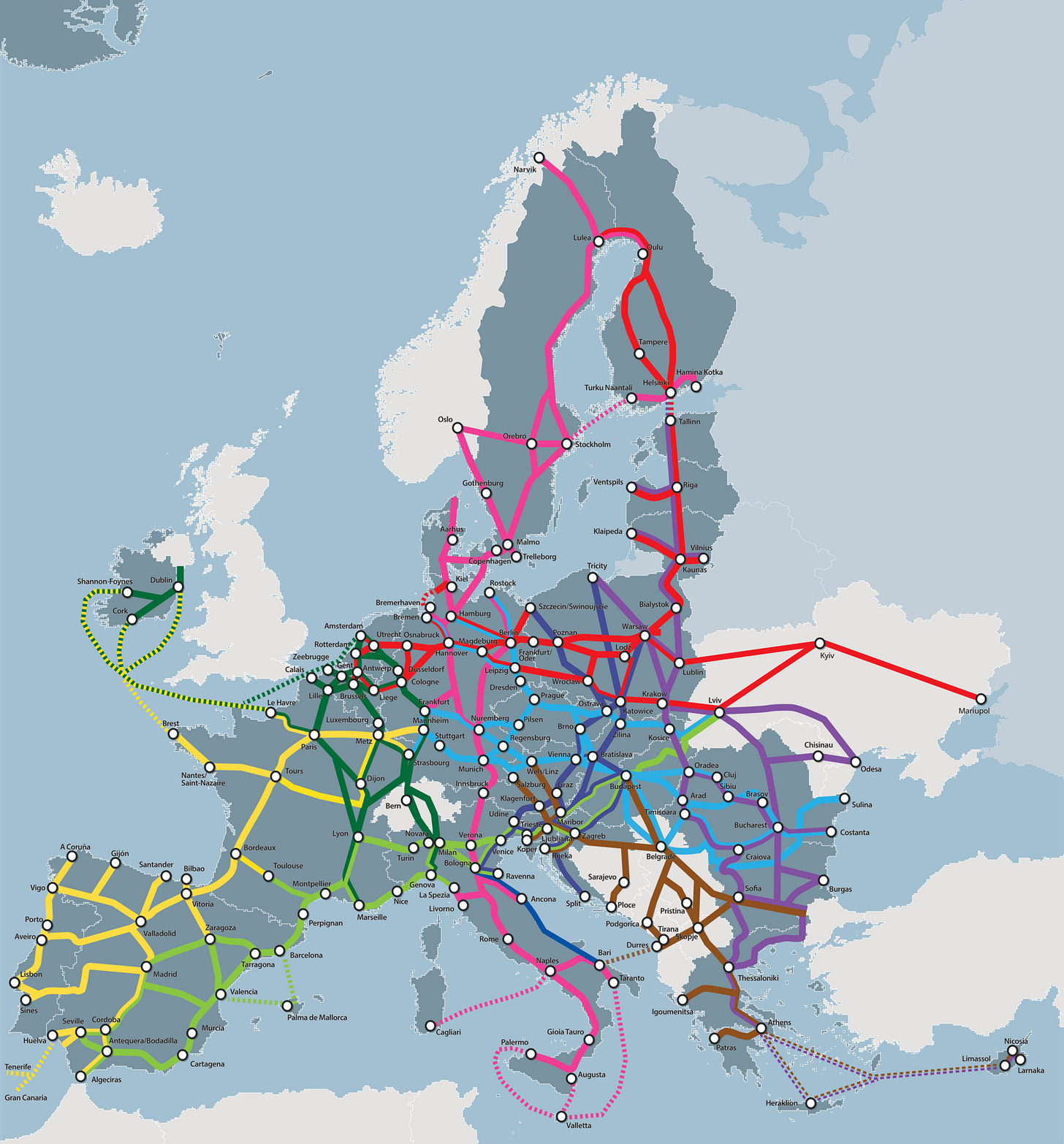

The Lyon-Turin high-speed rail project is part of the European Union's TEN-T network, specifically the Mediterranean Corridor (the green line in the map below) that will eventually link Algeciras in Spain to Budapest in Hungary.

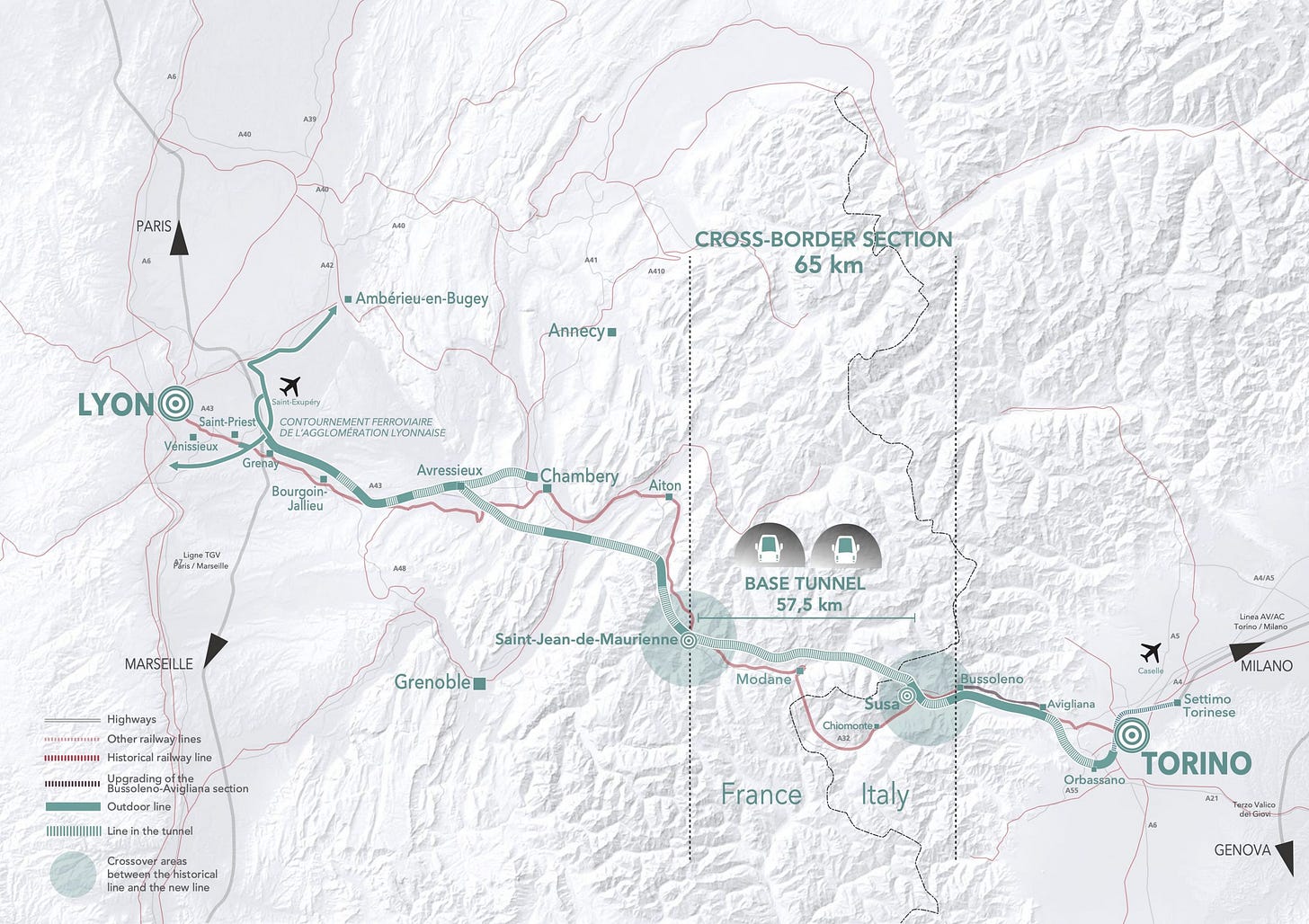

Spanning 270 kilometers, the new line aims to improve both passenger and freight transport between Italy and France.

First conceived in the early 1990s, the project has undergone numerous feasibility studies, redesigns, and political battles. What began as a proposal for faster passenger trains has evolved into a crucial component of Europe's climate strategy.

When completed, the journey time between Milan and Paris will be slashed from seven hours to just four, making rail competitive with air travel for the first time on this route. The line is also expected to remove more than one million lorries from Alpine roads annually.From mountain passes to lowland railways

Another primary motivation for the Lyon-Turin project is to transform freight transport across the Alps. Currently, almost 44 million tonnes of goods cross the Western Alps annually, with more than 90% traveling by road.

The world’s longest railway tunnel

The centerpiece of the project is the 57.5-kilometer Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel —which will surpass Switzerland's 57.1-kilometer Gotthard Base Tunnel to become the world's longest railway tunnel.

The tunnel will connect Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in France's Maurienne valley with Susa in Italy's Piedmont region. Currently, trains between France and Italy must climb the Mont Cenis mountain on gradients of up to 30% to a height of 1,338 meters, requiring up to three locomotives to haul the trains.

In contrast, the new base tunnel will feature a maximum gradient of just 12.5% and a maximum altitude of 580 meters. This flatter profile will allow heavy freight trains to transit at 100 km/h and passenger trains at 220 km/h, while reducing energy consumption by approximately 40%.

Seven giants boring through a mountain

To build the tunnel, seven giant tunnel boring machines (TBMs) will excavate 85km of the 115km twin-tube length. According to TELT's project director Alexandre Heim, there are 14 different types of ground conditions along the tunnel route, ranging from loose ground at the French side to highly challenging schist and gneiss formations with high overburdens between Modane and the Italian border.

For sections near the French tunnel entrance, where loose ground makes TBMs impractical, engineers are employing the New Austrian Tunnelling Method (NATM), also known as the Sequential Excavation Method. This technique integrates the surrounding rock or soil formations into an overall ring-like support structure, with the formations themselves becoming part of the supporting structure.

In total, the project will involve excavating an astonishing 162 kilometers of tunnels, including two parallel main tunnels, four shafts, and 204 safety bypasses. So far, approximately 39.5 kilometers of exploratory and service tunnels have been completed.

The €25 billion question

The financing of this megaproject is complex. The total cost of the Lyon-Turin line is estimated at €25 billion, with the international section alone (including the base tunnel) costing €11 billion as of 2024 estimates — up from the original €8 billion estimate in 2016.

Funding is shared between the European Union, which contributes 40% of the tunnel costs, Italy (34.7%), and France (25.26%). The EU has indicated willingness to increase its contribution to 55%, as well as to help fund the French access routes if they go beyond mere adaptations of existing infrastructure.

This massive investment has been subject to intense scrutiny. In 2012, the French Court of Audit questioned the reliability of cost estimates and projected traffic volumes. The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) has investigated allegations of cost overruns, potential mafia infiltration, and conflicts of interest.

In Italy, the Five Star Movement strongly opposed the project while their coalition partner, the League party, firmly supported it. This internal conflict within the Italian government reached a crisis point in March 2019 when Italy's Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte officially requested TELT to stop the launch of tenders for further construction work.

Despite these challenges, funding has continued to flow. In January 2024, just before an EU deadline, the French national government and various local entities reached a last-minute agreement on their respective contributions to studies for the French section, preventing the loss of additional EU support.

The puzzle of why Lyon may wait until 2045

Perhaps the most puzzling aspect of the Lyon-Turin project is the disconnect between completion timelines for different sections. While the Mont d'Ambin base tunnel is scheduled for completion by 2032, the access routes on the French side might not be ready until 2045 — more than a decade later.

This discrepancy stems from the French government appearing more inclined to modernize the historic Dijon-Modane railway line, which doesn't pass through Lyon, rather than building new direct access routes as originally planned.

This means Dijon might get access to the tunnel long before Lyon does, contradicting the original project design and potentially limiting its effectiveness. The railway lines from Lyon to the tunnel might not be complete for another thirteen years after the tunnel opens, creating a bizarre situation where the centerpiece of the project is finished but cannot be fully used.

This week on the podcast

This week on the podcast, our hosts analyze the Toulouse Metro Line C Expansion, a €3.4 billion project using innovative variable density tunnel boring machines to create a 27km line combining underground tunnels and elevated viaduct sections.

They also discuss Autodesk's restructuring, which saw 1,350 employees laid off as the company shifts to a self-serve model, and debate whether construction software provides genuine competitive advantage or simply becomes a necessary tax for staying in business.