Can a new administrative capital solve Cairo’s chronic overpopulation?

Egypt has moved its administration to a vast, futuristic city 45 kilometres down the road from Cairo.

Welcome back to The Off Site, brought to you by Aphex.

From Dubai’s 2040 Urban Master Plan to Tanzania’s Bagamoyo Port and Saudi Arabia’s trillion-dollar megacity ‘The Line’, North Africa and the Middle East are home to hugely ambitious infrastructure proposals.

These monuments inject jobs, foreign investment, and infrastructure into local economies, but they also contribute to the type of stories these countries want to tell about themselves: their national identity, and their international reputation.

Egypt’s New Administrative Capital (NAC) is a prime example. Egypt has built satellite cities to Cairo before, mostly between the 70s to 90s. But the NAC is unique in its scope and grandeur.

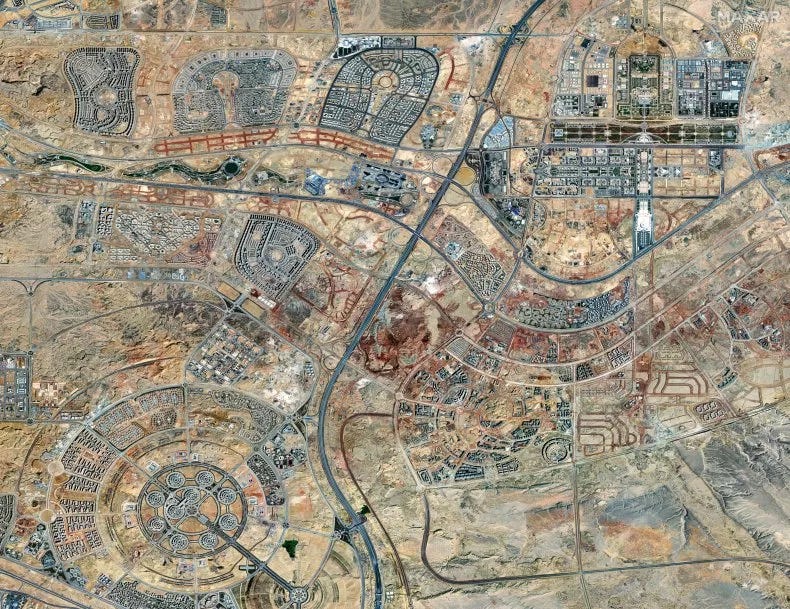

Announced in March 2015, the NAC is already sprawling across an area about the same size as Singapore’s main island. From the largest cathedral in the Middle East to a proposed kilometre-high obelisk, the NAC is following through on some sky-high claims.

Why build a new capital?

Cairo is one of the biggest cities in the world. Like other global capitals, it has struggled for decades with overpopulation, congestion, limited housing, and social unrest.

In 2016, Egypt launched a national agenda called ‘Vision 2030’ as the cornerstone of its development efforts. A central part of Vision 2030 is the NAC: a new capital featuring the majority of Egypt’s legislative, governance, and military administration, 45 kilometres away from Cairo.

But it’s about more than just sending the bureaucrats down the road. The NAC proposal includes 25 residential neighbourhoods, designed with access to green spaces and other quality of life measures in mind. And huge proposed structures like the Oblisco Capitale building will reportedly be home to extensive shopping, residential, and entertainment spaces. Although the exact number has shifted across the NAC’s development, it eventually hopes to be home to about 5 million of Cairo’s current residents.

A modern desert city

Because the site is in a previously undeveloped desert, building a metropolis from scratch has presented some particular logistical challenges. All basic infrastructure — power, water, telecommunications, and transport — had to be established before any buildings could rise.

And the engineering scale is vast: 10,000 kilometers of roads were planned for Phase 1 alone, plus utility networks spanning the entire development area.

Cairo itself is mostly built on rich alluvial soils proximate to the Nile, but its new satellite cities extend into deserts and plateaus. There, the low cohesion and high permeability of the sandy soil means it has a high risk of differential settlement that requires soil improvement for cultivation, and deep foundations for construction.

Construction also means dealing with extreme temperature variations, sand infiltration, and soil subsidence under heavy loads.

What's actually been built

Construction on the NAC has currently been completed across 40,000 feddans (168km2) of desert. Public servants are already working in the new government district, home to Egypt's cabinet, parliament, and various ministries. The Central Business District also has multiple completed office towers, including the 385.8-meter Iconic Tower — now Africa's tallest building.

Residential areas are taking shape too. Better Home Group recently completed its Midtown Solo project, with standalone villas targeting high-end buyers. 95% of infrastructure works for Phase 1 are reportedly complete, with final utility connections pending developer compliance.

This is less than a quarter of the total planned development. Phases 2-4 will expand across another 770 square kilometres, although their start has been delayed until 2026 while the government focuses on completing current work.

Coordination across the capital

The Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD) oversees the entire project. The Ministry of Housing holds 49% of ACUD’s ownership, while the military holds 51%. Among other things, the military’s involvement provides access to cheap labor through conscripts and control over key supply chains like steel and cement.

While ACUD takes the primary oversight role, two key firms have been involved in day-to-day management and design.

US architecture firm SOM developed the NAC’s initial master plan. International consultancy Dar al-Handasah Shair & Partners has now taken over detailed planning.

Dar was involved with the entire CBD design process, the Capital Park Development Corridor master plan, and supervision of the Governmental District construction. For Phases 2-4, Dar will handle everything from roads and utility networks to "future-fitness strategies" that incorporate AI integration.

Smart city surveillance

As with many other new, from-scratch cities, the NAC wants to integrate smart features. So far, this involves extensive and comprehensive civilian monitoring.

A surveillance system delivered by Honeywell promises to “monitor crowds and traffic congestion, detect incidents of theft, observe suspicious people or objects, and trigger automated alarms in emergency situations.” Residents will use smart cards and apps for everything from unlocking doors to making payments, and public WiFi will be beamed from lamp posts.

Technology contracts have already delivered a bill of USD 640 million. Later phases involving Huawei, Orange, and Mastercard could push the investment to $900 million.

This intensified surveillance highlights another reason for moving state administration out of the densely populated capital: it’s harder to mobilise a mass protest when the government is 45 kilometres down the road. Even if protestors got to the NAC, walking across its vast expanse would take hours.

The money question

The NAC’s $58 billion price tag raises obvious questions about priorities. Most Egyptians can't afford to live in the capital being built in their name: two-bedroom apartments in the city cost around $50,000 in a country where GDP per capita sits below $3,000 annually. On the other hand, the vast array of construction needs creates jobs across Egypt's struggling industries.

In the centre of these conversations — and the centre of the NAC — is the proposed Oblisco Capitale. A kilometre high and heavy with symbols of Egyptian national identity, it aims to usurp the Burj Khalifa as the tallest building in the world.

Announcements about the Oblisco date back to 2018, situating it within Vision 2030 principles of ‘human-centred development’ and ‘well-developed infrastructure’. Although it’s generated significant media buzz, it hasn't progressed beyond architectural renderings from Egyptian firm IDIA. Ground hasn't been broken, tenders haven't been issued, and no construction timeline has been released.

Turning architectural ambition into concrete reality obviously requires more than dramatic renderings. But, as the Iconic Tower (and the whole NAC) proves, Egypt is more than capable of delivering grand infrastructure projects when resources align with its political priorities.

On the pod

This week, the team tackles the global rise of megaprojects, the revolution in AI browsers, and the UK infrastructure wave. Enjoy!